The Dhamma In Clouds

And the spiritual benefits of recollecting them

Moving on from last month’s somber post, I’d like to explore a topic relegated to obscurity in Western Buddhist circles, focusing on less metaphysical concepts. Tucked away in the dense exposition of the Saṃyutta Nikāya lies a tetrad of chapters (SN 29-32) on earthy celestial beings: Nāgas (dragons), Supaṇṇas (birds), Gandhabbas (musicians), and lastly, the subject of this article: Valāhakas (cloud devas)1.

As Bhikkhu Bodhi explains, “These are devas living in space who have arisen in the company of the devas called the cloud dwellers.” (CDB 1102).

The conception of weather-directing spirits has a substantial impact on Buddhist cultures worldwide. This is something Alexandra Cain, M.Div, covers in her article “What Is Buddhist Magic?”

In this post, I’d like to take a deep dive into this concept within the vast world of early Buddhism. Why has an entire chapter of a Nikāya been dedicated to expounding the specifics of a certain denomination of earth devas?

Is it just world-building, taken to be discarded as metaphysical baggage?

I want to challenge this very notion: that we can discard cosmological teaching simply because they don’t seem ‘deep enough’ or because they are unconducive to practice. As someone coming to Buddhist teachings from a secular background, many of us are conditioned to view metaphysical teachings as beneath us, holding an antagonistic attitude towards anyone who dares to ponder if there’s something more out there. Admittedly, I’m still rather agnostic about such matters. I’m not trying to prove the existence of celestial beings; this I see as an entirely unproductive endeavor. Additionally, it was never the aim of the Buddha to ‘prove’ anything. He was a teacher who expounded on the nature of the world, not to prove that there is suffering and a cessation of suffering, but rather to allude to this truth to those with little dust in their eyes (MN 26). It’s ultimately a matter of personal faith, and you can decide for yourself whether to believe in the cosmology or not.

The elitist Western consciousness views these concepts as baggage, a hindrance to the real meat of Dhamma. As Alexandra Cain writes, “We love to trim things down. Clean it up. Take the parts that feel scientific or soothing and leave the rest behind.” However, one must then ask, isn’t this precisely what the Buddha advised against? I.e., to reject views solely based on incompatibility with pre-held notions? Those who put a secular materialistic worldview on a pedestal as the ‘most rational’ and disregard all else that doesn’t accord, engage in the blind dogma that they claim to stand against2.

To get the full picture of Buddhism, one must take into consideration the entire canonical context, not just what seems convenient.

I hope to allude just to that: all concepts, regardless of their perceived importance, are worth learning about. The Valāhakas contain a wealth of Dhamma, not merely a worldbuilding deadweight. With that out of the way, let’s explore the fascinating world of the devas of the cloud-dwelling order and what it holds (no pun intended;)) for practice.

Cosmology Of The Cloud Devas (Valāhakas)

Valāhakas are divided into five orders3:

Cool-Cloud Devas (sīta-valāhakā devā)

Warm-Cloud Devas (uṇha-valāhakā devā)

Storm-Cloud Devas (abbha-valāhakā devā)

Wind-Cloud Devas (vāta-valāhakā devā)

Rain-Cloud Devas (vassa-valāhakā devā)

It’s assumed that Valāhakas are spontaneously born, given that no canonical texts mention otherwise. Their interaction within the larger worldview is demonstrated in some texts; the crux is given in this template:

“Venerable sir, what is the cause and reason why it sometimes becomes [One of the 5 weather conditions paired with their respective cloud deva order]? There are, bhikkhu, what are called [One of the 5 cloud deva orders]. When it occurs to them, 'Let us revel in our own kind of delight4,' then, in accordance with their wish, it becomes [One of the 5 weather conditions paired with their respective cloud deva order]. This, bhikkhu, is the cause and reason why it sometimes becomes [One of the 5 weather conditions paired with their respective Devā order]."

SN 32.53-57

Punnadhammo Mahāthero gives perhaps the most comprehensive account of Valāhakas:

“During the hot season they do not like to stir from their vimānas, it being too hot to play, hence it does not rain, “even a single drop” (DN-a 27). These devas, however, are not the sole cause of the weather; the commentary lists seven: the power of nāgas, the power of supaṇṇas, the power of devas, the power of an assertion of truth, natural weather (utusamuṭṭhāna- lit. caused by temperature), the workings of Māra and supernormal power (SN-a 32:1). The subcommentary explains that normal seasonal changes are simply the work of natural processes, but unusual weather is caused by action of these devas. It is also said that the morality of human beings has an indirect effect on the weather; by causing the sky devas to become either pleased or annoyed. When the state of human morality is good the devas are pleased and the rain falls regularly in due season; when human morality is bad, the devas are displeased and withhold the rains (AN 4: 70)5. However, it may also happen that the cloud devas are simply distracted by play and become heedless (AN-a 5: 197) because they are, after all, beings of the plane of sense desire. As this is said to be among the causes of failure of the rains which the prognosticators (nemitta) do not know and cannot see, it may explain why weather forecasts are so often wrong!”

THE BUDDHIST COSMOS: A Comprehensive Survey of the Early Buddhist Worldview, according to Theravāda and Sarvāstivāda sources (p.g. 270)

The Valāhakas, much like any other type of deva, aren’t all benevolent. Accounts are given of the devas using their weather-altering powers through wholesome (kusala) and unwholesome (akusala) means. The Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (DN 16) recounts an account of “the rain-god,” most likely referring to Pajjunna, the ruler of rain clouds (although not explicitly mentioned), who either directly or indirectly brings about the deaths of four humans and four bulls.

“Once, Pukkusa, when I[The Buddha referring to himself] was staying at Atuma, at the threshing-floor, the rain-god streamed and splashed, lightning flashed and thunder crashed, and two farmers, brothers, and four oxen were killed.”

DN 16

Other texts recount a more compassionate Pajjunna who acts as a savior, as will be shown later on (Ja-a 75).

The Mighty Water Dharaṇī

The Atānātiya Sutta includes this interesting detail:

“There's the mighty water Dharaṇī,

Source of rain-clouds which pour down When the rainy season comes.”

DN 32

While the verse doesn’t directly mention cloud devas, it could potentially elucidate the metaphysical inner workings of how Valāhakas function: The mighty water Dharaṇī6 of northern Kuru7 provides sustenance for the rain and storm cloud devas, which they use to ‘stream and splash’ about in our presence.

Clouds In The Āgamas

The Āgamas are the Chinese parallel texts to the Nikāyas, originating from the Sarvāstivāda, Dharmaguptaka, Kāśyapīya, etc., schools of early Buddhism, which are now extinct. While the collections are completely separate from the Theravādan canon, they are still widely regarded as early Buddhist texts.

This excerpt from the Description of the World (Loka-viveka) Sūtra provides an account of a Nāga king harnessing the power of rain clouds, potentially suggesting that other powerful earth-dwelling celestial beings under the domain of the four great kings can also wield power over rain cloud devas.

“the nāga king8 causes fresh clouds to waft up and permeate the sky, with rainshowers falling like drops of nectar to the herds of cattle below. The liquid itself is rich, blending eight distinct tastes. Just as a garland maker scatters water over his flowers to keep them fresh and prevent withering, the water does not linger on the ground in puddles, so muddy roads cannot form..

When the cakravartin9 rules the world, the nāga king of Anavatapta Lake10 causes heavy clouds to rise and permeate the sky after midnight, and rainshowers to fall to the cattle being herded below. The abundant rainwater, blending eight distinct tastes, falls everywhere. And just as a garland maker scatters water over his flowers to keep them fresh without withering, the copious rain causes the grasses and trees to grow luxuriantly, without any standing water to form puddles or muddy roads.”

DĀ 30

Other excerpts from the same Sūtra highlight more potential metaphysical functions of the Valāhakas.

“There are three reasons given for the saltiness of seawater. What are the three? First, clouds spontaneously appeared and filled the sky as far as Ābhāsvara Heaven [Devas of streaming radiance (Ābhassara Deva-loka)], pouring down rain all around. The rain washed over the celestial palaces and thoroughly cleansed everything under the sky, from the palaces of the Brahmakāyika gods[The first three Brahma realms (Brahmakāyika Deva-loka)], the Paranirmitavaśavartin gods[Devas wielding power over others’ creations (Paranimmita-vasavatti Deva-loka)], and the Yama gods[Yama devas (Yāma Deva-loka)] to the four continents and the eighty thousand mountains and mountain ranges, including Mount Sumeru[Pali: Sineru]…

DĀ 30

For context, the next excerpt details the Asura vs. Tāvatiṃsa war; a conflict pitting the Asura titans against the Devas aligned with the Tāvatiṃsa devas, the latter of which have the four great kings and their underlings as allies (which the cloud devas fall under the domain of). It would appear that the Valāhakas are one of the first lines of defence against the asuras.

Then Rāhu, king of the asuras11, prepared his weapons, donned hisarmor, and rode out in his chariot to lead the hundreds of thousands of asura legions to battle. By this time, the nāga kings Nanda and Upananda had encircled Mount Sumeru with their bodies seven times for defense, shaking the hills and valleys, unleashing rain from an increasingly overcast sky, and slapping the ocean surface with their tails to send the water high over the top of Mount Sumeru. The Trāyastriṃśa gods[The 33 gods (Tāvatiṃsa Devas)] thought, ‘The clouds are growing, rain is falling, the ocean is stirring, and the waves are reaching us here. This can only mean that the asuras are coming.’ Now the asuras met a host of nāgas from the ocean, innumerable myriads in heavy armor and carrying pikes, bows and arrows, spears and lances, and daggers and swords”

DĀ 30

There are multiple other accounts of clouds within this Sūtra alone. See this free online edition.

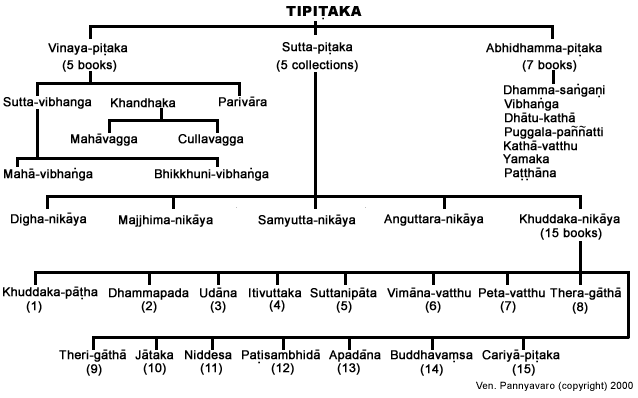

Rulership Structure

Generally speaking, Valāhakas fall under the domain of the Four Great Kings (Cātumahārājikā), specifically under the reign of Vessavaṇa12, king of the northern quarter and lord of Yakkhas13 (DN 20). Pajjuna is a cloud deva with kingship over storm and rain cloud devas14. Sakka15 has direct authority over the Four Great Kings, as well as all subordinate celestial beings16.

Green = Sakka, king of the Tāvatiṃsa realm (heaven of the 33 gods)

Blue = Realm of the Four Great Kings

Red = Vessavaṇa, also known as Kuvera; one of the four great kings, ruling over the northern quarter

Orange = The 5 orders of cloud devas

Yellow = Pajjunna, ruler of the rain and storm cloud devas

Dark Grey = Storm cloud devas and rain cloud devas

Pajjunna, Ruler Of Storm And Rain Cloud Devas

Pajjunna receives rare canonical mention17; however, just enough exposition is given to flesh out a basic picture.

“Pajunna18

The Thunderer, who also causes rain.”

DN 20

In the Āṭānāṭiya Sutta (DN 32), Pajjunna is listed in the Āṭānāṭā protective verses as one of the “yakkhas, the great yakkhas, their commanders and commanders-in-chief” which a disciple of the Buddha can call out in times of harassment by celestial beings19.

“Now if any yakkha or yakkha-off spring, . . . gandhabba, . . . should approach any monk, nun, male or female lay-follower. . .with hostile intent, that person should alarm, call out and shout to those yakkhas, the great yakkhas, their commanders and commanders-in-chief, saying: ‘This yakkha has seized me, has hurt me, harmed me, injured me, and will not let me go!’

'Which are the yakkhas, the great yakkhas, their commanders and commanders-in-chief? They are:

…Pajunna…”

DN 32

The Jātaka verses20 include two verses worth noting, one directly invoking Pajjunna by name, the other potentially alluding to him:

“Thunder, Pajjuna, destroy the trove of the crows, oppress the crow with grief, free me and mine from grief.”

“God brought a mighty cloud wherefrom he sent a shower of rain”

The Jātaka-aṭṭhakathā (commentarial text on the Jātaka verses) described a much more expansive background; however, it should be noted that these texts are not canonical, as only the verses themselves shown above are part of the actual Jātaka (a specific name given to a collection of poems in the Sutta Piṭaka’s Khuddaka Nikāya21. The relevant commentarial exposition from Ja-a 75 and Ja-a 547 is below, but to summarize, the former details two accounts: one of Sakka commanding Pajjunna to fill the tank of Jetavana so that the Buddha can bathe, and another of the Bodhisatta as a fish praying to Pajjunna to save his fish friends from getting eaten alive by crows, due to drought leaving them bare. The latter recounts the Bodhisatta as a king exiled for his overgenerosity; due to his extraordinary display of virtue, Sakka himself produced rain to alleviate the drought that the Bodhisatta and his attendants had succumbed to. Afterward, the Bodhisatta and his retinue were welcomed back to his kingdom with open arms.

“‘Bring me a bathing-dress, Ānanda22; for I would bathe in the tank of Jetavana.’ ‘But surely, sir,’ replied the elder, ‘the water is all dried up, and only mud is left.’ ‘Great is a Buddha’s power, Ānanda. Go, bring me the bathing-dress,’ said the Teacher. So the elder went and brought the bathing-dress, which the Teacher donned, using one end to go round his waist, and covering his body up with the other. So clad, he took his stand upon the tank-steps, and exclaimed, ‘I would willingly bathe in the tank of Jetavana.’

That instant the yellow-stone throne of Sakka grew hot beneath him23, and he sought to discover the cause. Realising what was the matter, he summoned the king of the Storm-Clouds, and said: ‘The Teacher is standing on the steps of the tank of Jetavana, and wishes to bathe. Make haste and pour down rain in a single torrent over all the kingdom of Kosala.’ Obedient to Sakka’s command, the king of the Storm-Clouds clad himself in one cloud as an under garment, and another cloud as an outer garment, and chanting the rain-song, he darted forth eastward. And lo! he appeared in the east as a cloud of the size of a threshing-floor, which grew and grew till it was as big as a hundred, as a thousand, threshing-floors; and he thundered and lightened, and bending down his face and mouth deluged all Kosala with torrents of rain. Unbroken was the downpour, quickly filling the tank of Jetavana, and stopping only when the water was level with the topmost step. Then the Teacher bathed in the tank…

‘This is not the first time, monks,’ said the Teacher, ‘that the Tathāgata has made the rain to fall in the hour of general need. He did the like when born into the brute-creation, in the days when he was king of the fish.’ And so saying, he told this story of the past:

In the past, in this self-same kingdom of Kosala and at Sāvatthi too, there was a pond where the tank of Jetavana now is – a pond fenced in by a tangle of climbing plants. Therein dwelt the Bodhisatta, who had come to life as a fish in those days. And, then as now, there was a drought in the land; the crops withered; water gave out in tank and pool; and the fishes and turtles buried themselves in the mud. Likewise, when the fishes and turtles of this pond had hidden themselves in its mud, the crows and other birds, flocking to the spot, picked them out with their beaks and devoured them. Seeing the fate of his kinsfolk, and knowing that none but he could save them in their hour of need, the Bodhisatta resolved to make a solemn Assertion of Truth, and by its efficacy to make rain fall from the heavens so as to save his kinsfolk from certain death. So, parting asunder the black mud, he came forth – a mighty fish, blackened with mud as a casket of the finest sandalwood which has been smeared with collyrium. Opening his eyes which were as washen rubies, and looking up to the heavens he thus bespoke Pajjunna, King of Devas, ‘My heart is heavy within me for my kinsfolk’s sake, my good Pajjunna. How comes it, pray, that, when I who am righteous am distressed for my kinsfolk, you send no rain from heaven? For I, though born where it is customary to prey on one’s kinsfolk, have never from my youth up devoured any fish, even of the size of a grain of rice; nor have I ever robbed a single living creature of its life. By the truth of this my Assertion, I call upon you to send rain and succour my kinsfolk.’ Therewithal, he called to Pajjunna, King of Devas, as a master might call to a servant, in this verse:

‘Thunder, Pajjuna, destroy the trove of the crows24, oppress the crow with grief25, free me and mine from grief.’”

“At that moment the hills resounded, the earth quaked, the great ocean was troubled, Sineru, king of mountains, bent down: the six abodes of the gods were all one mighty sound. Sakka, King of the Devas, perceived that six royal personages and their attendants lay senseless on the ground, and not one of them could arise and sprinkle the others with water; so he resolved to produce a shower of rain. This he did, so that those who wished to be wet were wet, and those who did not, not a drop of rain fell upon them, but the water ran off as it runs from a lotus-leaf. That rain was like rain that falls on a clump of lotus-lilies. The six royal persons were restored to their senses, and all the people cried out at the marvel, how the rain fell on the group of kinsfolk, and the great earth did quake.

This the Teacher explained as follows:

‘When these of kindred blood were met, a mighty sound outspake,

That all the hills reechoed round, and the great earth did quake.

God brought a mighty cloud wherefrom he sent a shower of rain,

When as the king Vessantara26 his kindred met again.

King, queen, and son, and daughter-in-law, and grandsons, all were there,

When they were met their flesh did creep with rising of the hair.

The people clapped their hands and loud made to the king a prayer:

They called upon Vessantara and Maddī, one and all:

‘Be you our lord, be king and queen, and listen to our call!’”

While the latter excerpt recounts Sakka as the one who directly manifests rain, the canonical verse itself refers only to a god27, escaping explicit mention. Given the poem’s overall context28, it’s more likely than not that the commentarial account is correct, but I will leave that to you to decide. Taking the parable at face value, it would seem that Sakka can not only command Valāhakas but control them himself29.

Both of these Jātaka tales reinforce how Valāhakas act in accordance with the morality of beings. The Āṭānāṭā protective verses are instructed only for followers of the Buddha; Pajjunna and his retinue of Abbha and Vassa Valāhakas respond to the prayers of virtuous beings such as the Bodhisatta. It’s also heavily implied that they can cause death or deadly suffering to those of immoral conduct, as with the crows.

Tension With Secular Doctrine

These extracts highlight perhaps a side of Theravada or EBT30 that practitioners often shy away from, in favor of internal alleviation of suffering (dukkha): praying to gods (In this case, Pajjunna) to succor those afflicted by evil beings. Parallels can be drawn here with tantric Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna practice, in which devotion to reciting mantras or prayers to Bodhisattvas for spiritual assistance is a key doctrine. This Tibetan excerpt is especially pertinent31:

“She is the Protectress from the Fear of Fire32. A certain householder hated his enemy (neighbour) and one night set fire to his house. The latter started to flee but could not get free—at that instant he called out, "O Tārā, O Mother Tārā” A beautiful blue cloud arose above the house, and from it felt a continual shower of rain, like a yoke, on the house itself, completely quenching the flames.”

Sarvatathāgatamātṛ Tārā Tantra (Toh 726, Degé Kangyur, rGyud ’bum); trans. David Templeman, The Origin of Tārā Tantra (Berkeley: Dharma Publishing, 1981) (p.g. 16)

To disregard these protective verses (paritta) as insignificant would be misguided; you can't just cherry-pick the Suttas that confirm your pre-held notions and ignore the rest, even if they don’t accord with Western secular sensibilities33. The occult is very much core to early Buddhism, and within this worldview, our existence is ripe with the influence of a plethora of celestial beings in all varieties. Therein, it would seem sensible to learn how to navigate the supernatural skillfully. In the case of the Āṭānāṭiya Sutta, the purport is fairly straightforward: those who follow the Buddha’s teachings (i.e., cultivate wholesome qualities and abandon the unwholesome) can effectively wield the verses as a tool against antagonism from ill-meaning devas. As one harboring hate (dosa) can cultivate loving-kindness (metta) as a tool of practice, one afflicted by malevolent Yakkhas34 can use the Āṭānāṭā Protective Verses to “dwell guarded, protected, unharmed and at their ease” (DN 32)35. It’s just another appliance in the wide assortment of the Buddha’s toolbox, albeit a more external one36. As with any other teaching, it should be practiced skillfully in its applicable context, nothing more, nothing less.

If you find this difficult to reconcile with a scientifically backed materialistic worldview37, that’s perfectly understandable, and anyone is free to accept and reject whatever teachings they see fit. However, one must not conflate personal takeaways with a reflection of wider doctrine. That’s not fundamentalist, but rather doctrinal clarity.

Pajjunna's Daughters

In the connected discourses with Devatās (devatāsaṃyutta) of the Saṃyutta Nikāya, two Suttas are devoted to Kokanadā and Cūlākokanadā, Pajjunna’s older and younger daughters, respectively. In these discourses, they are depicted as Devatās, earth-dwelling celestial beings38 who are both disciples of the Buddha.

“Then, when the night had advanced, Kokanadā, Pajjunna's daughter, of stunning beauty, illuminating the entire Great Wood, approached the Blessed One. Having approached, she paid homage to the Blessed One, stood to one side, and recited these verses in the presence of the Blessed One:

‘I worship the Buddha, the best of beings,

Dwelling in the woods at Vesali.

Kokanada am I,

Kokanada, Pajjunna's daughter…”

SN 1.39

“Then, when the night had advanced, Cūlā-kokanadā, Pajjunna's [younger] daughter[Same as in SN 1.39]…

‘Here came Kokanada, Pajjunna's daughter,

Beautiful as the gleam of lightning.

Venerating the Buddha and the Dhamma,

She spoke these verses full of meaning...”

SN 1.40

Pajjunna, Kokanadā, and Cūlā-kokanadā are the only named Valāhaka deities. Nothing is particularly of note about Pajjunna’s daughters, other than them being Dhamma devotees.

Cause for Rebirth Among The Cloud Devas (Valāhakas)

Conduct conducive to rebirth among Valāhakas can be condensed into four general categories:

Good conduct of body (kāyena sucaritaṃ), speech (vācāya sucaritaṃ), and mind (manasā sucaritaṃ).

Giving various gifts(dāna).

Observing the Uposatha39.

Setting the intention (adhiṭṭhāna) for rebirth specifically in the company of devas of the cloud-dwelling order40.

Except for the fourth factor, these practices aren’t all required, but rather merely the setting of intention, and sufficient diligence with any one of the other three.

Good Conduct (Sucarita)

"Venerable sir, what is the cause and reason why someone here, with the breakup of the body, after death, is reborn in the company of the devas of the cloud-dwelling order? Here, bhikkhu, someone practises good41 conduct of body, speech, and mind. He has heard: 'The devas of the cloud-dwelling order are long-lived, beautiful, and abound in happiness.' He thinks: 'Oh, with the breakup of the body, after death, may I be reborn in the company of the devas of the cloud-dwelling order42!' Then, with the breakup of the body, after death, he is reborn in the company of the devas of the cloud-dwelling order.”

SN 32.2

This categorization is the threefold good conduct (tividha sucarita). The triad is further expanded into the ten courses of wholesome action (dasa kusala-kammapathā), the foundation for lay Buddhist ethics43:

Good Conduct By Body (Kāyasucarita):

Abandoning the destruction of life (pāṇātipātā pahāya).

Abandoning the taking of what is not given (adinnādānā pahāya).

Abandoning sexual misconduct (kāmesumicchācārā pahāya).

Good Conduct By Speech (Vacīsucarita):

Abandoning false speech (musāvāda pahāya).

Abandoning divisive speech (pisuṇāvācā pahāya).

Abandoning harsh speech (pharusāvācā pahāya).

Abandoning idle chatter (samphappalāpa pahāya).

Good Conduct By Mind (Manosucarita):

Abandoning the longing for the wealth and prosperity of others (anabhijjhā).

Abandoning hate and cultivating goodwill (abyāpāda).

Right view (sammādiṭṭhi).

Intriguingly, only four of the first five precepts (pañca sikkhāpada) are mentioned in the list, excluding the abandoning of liquor, wine, and intoxicants (surāmerayamajjapamādaṭṭhānā veramaṇī)44. However, it could be argued that one with the right view would see the danger in this indulgence45.

In the ending of the Cunda Kammaraputta Sutta, it’s explicitly stated that following the tenfold good conduct results in a heavenly destination:

“It is because people engage in these ten courses of wholesome kamma that the devas, human beings, and other good destinations are seen.”

AN 10.176

Giving (Dāna)

[Same as in SN 32.2].… "He thinks: 'Oh, with the breakup of the body, after death, may I be reborn in the company of [One of the 5 cloud deva orders]!' He gives food.... He gives drink.... He gives clothing.... He gives a vehicle…. He gives a garland.... He gives a fragrance…. He gives an unguent.... He gives a bed…. He gives a dwelling…. He gives a lamp46. Then, with the breakup of the body, after death, he is reborn in the company of [One of the 5 cloud deva orders].

SN 32.3-52

A multitude of suttas elaborate on the various aspects of giving; however, I will cite what is most pertinent47:

“Bhikkhus, there are these five benefits of giving. What five? (1) One is dear and agreeable to many people. (2) Good persons resort to one. (3) One acquires a good reputation. (4) One is not deficient in the layperson’s duties. (5) With the breakup of the body, after death, one is reborn in a good destination, in a heavenly world. These are the five benefits in giving.”

AN 5.35

“Here, Sariputta, someone gives a gift with expectations, with a bound mind, looking for rewards; he gives a gift, (thinking): ‘Having passed away, I will make use of this.’ He gives that gift to an ascetic or a brahmin48: food and drink; clothing and vehicles; garlands, scents, and unguents; bedding, dwellings, and lighting. What do you think, Sariputta? Might someone give such a gift?’

‘Yes, Bhante.’

‘In that case, Sariputta, he gives a gift with expectations, with a bound mind, looking for rewards; he gives a gift, (thinking): ‘Having passed away, I will make use of this.’ Having given such a gift, with the breakup of the body, after death, he is reborn in companionship with the devas (ruled by) the four great kings. Having exhausted that kamma, psychic potency, glory, and authority, he comes back and returns to this state of being.

‘But, Sariputta, someone does not give a gift with expectations, with a bound mind, looking for rewards; he does not give a gift, (thinking): ‘Having passed away, I will make use of this.’ Rather, he gives a gift, [thinking]: ‘Giving is good… [Same as in the first paragraph]…[Corresponds to rebirth in the Tāvatiṃsa realm, and then returning to a state of being (i.e., still bound to Saṃsāra)]…

…rather he gives a gift, (thinking): ‘Giving was practiced before by my father and forefathers; I should not abandon this ancient family custom.’... [Same as in the first paragraph]…[Corresponds to rebirth in the Yāma realm, and then returning to a state of being (i.e., still bound to Saṃsāra)]…

…rather he gives a gift, (thinking): ‘I cook; these people do not cook. It isn’t right that I who cook should not give to those who do not cook.’... [Same as in the first paragraph]…[Corresponds to rebirth in the Tusita realm, and then returning to a state of being (i.e., still bound to Saṃsāra)]…

…rather he gives a gift, (thinking): ‘Just as the seers of old—that is, Atthaka, Vimaka, Vamadeva, Vessamitta, Yamataggi, Angirasa, Bharadvaja, Vasettha, Kassapa, and Bhagu49—held those great sacrifices, so I will share a gift.’... [Same as in the first paragraph]…[Corresponds to rebirth in the realm of Devas delighting in creation (Nimmānaratī), and then returning to a state of being (i.e., still bound to Saṃsāra)]…

…rather he gives a gift, (thinking): ‘When I am giving a gift my mind becomes placid, and elation and joy arise.’... [Same as in the first paragraph]…[Corresponds to rebirth in the realm of Devas wielding power over others’ creations (Paranimmitavasavattī), and then returning to a state of being (i.e., still bound to Saṃsāra)]…

…rather, he gives a gift, (thinking): ‘It’s an ornament of the mind, an accessory of the mind50.’ Having given such a gift, with the breakup of the body, after death, he is reborn in companionship with the devas of Brahma’s company. Having exhausted that kamma, psychic potency, glory, and authority, he does not come back and return to this state of being [i.e., a non-returner (anāgāmī)].

AN 7.52

In the latter excerpt, the seven types of intention (cetanā) behind giving are elaborated, each one progressively leading to a loftier abode. As was covered previously, the cloud devas are ruled by the four great kings (cātumahārājikā)51. This demonstrates that the act of giving itself, even if the intention is rather self-serving, produces fruit in heavenly rebirth. It goes without saying that one should aspire to more altruistic motives; however, the key takeaway here is that generosity is always beneficial for yourself and others. There’s no such thing as ‘wrong generosity’, that is, within the context of mundane articles of monastic or lay life52.

Uposatha Observance

As laid out in AN 3.70, the eight observances taken on by the laity four times a month go as follows:

(1) “I too shall abandon and abstain from the destruction of life…

(2) I too shall abandon and abstain from taking what is not given…

(3) I too shall abandon sexual activity and observe celibacy…

(4) I too shall abandon and abstain from false speech…

(5) I too shall abandon and abstain from liquor, wine, and intoxicants, the basis for heedlessness…

(6) I too shall eat once a day, abstaining from eating at night and from food outside the proper time [after noon]…

(7) I too shall abstain from dancing, singing, instrumental music, and unsuitable shows, and from adorning and beautifying myself by wearing garlands and applying scents and unguents…

(8) I too shall abandon and abstain from the use of high and luxurious beds…”

AN 3.70

A later excerpt from the same Sutta explains how effective the observance is in generating a heavenly rebirth:

“To what extent is it[The Uposatha observance] of great fruit and benefit? To what extent is it extraordinarily brilliant and pervasive? Suppose, Visakha, one were to exercise sovereignty and kingship over these sixteen great countries abounding in the seven precious substances, that is, (the countries of) the Angans, the Magadhans, the Kasis, the Kosalans, the Vajjis, the Mallas, the Cetis, the Vangas, the Kurus, the Paficalas, the Macchas, the Surasenas, the Assakas, the Avantis, the Gandhdarans, and the Kambojans: this would not be worth a sixteenth part of the uposatha observance complete in those eight factors. For what reason? Because human kingship is poor compared to celestial happiness.

For the devas (ruled by) the four great kings, a single night and day is equivalent to fifty human years; thirty such days make up a month, and twelve such months make up a year. The life span of the devas (ruled by) the four great kings is five hundred such celestial years53. It is possible, Visakha, that a woman or man here who observes the uposatha complete in these eight factors will, with the breakup of the body, after death, be reborn in companionship with the devas (ruled by) the four great kings. It was with reference to this that I said human kingship is poor compared to celestial happiness.”

AN 3.70

The analogy here is striking, underscoring how the merit obtained from a Uposatha observance itself is conducive to heavenly rebirth. This would make the practice perhaps the most kammically potent of the first three factors, but also the most intensive, requiring the participant to devote the entire day to near-complete abstention from sensual pleasures54.

Setting The Intention (Adhiṭṭhāna)

In the Dānūpapatti Sutta, explicit mention is given to the fixed determination on a specific trajectory of rebirth:

“Oh, with the breakup of the body, after death, may I be reborn in companionship with the devas [ruled by] the four great kings!’ He sets his mind on this, fixes his mind on this, and develops this state of mind. That aspiration of his, resolved on what is inferior, not developed higher, leads to rebirth there. With the breakup of the body, after death, he is reborn in companionship with the devas (ruled by) the four great kings—and that is for one who is virtuous, I say, not for one who is immoral. The heart’s wish of one who is virtuous succeeds because of his purity.”

AN 8.35

This makes setting intention and its subsequent development perhaps the most decisive factor in the quartet.

As with the Noble Eightfold Path (ariya-aṭṭhaṅgika-magga) to enlightenment (bodhi), we can outline a path for rebirth among Valāhakas55:

Setting the explicit intention (adhiṭṭhāna)[i.e., ‘Oh, with the breakup of the body, after death, may I be reborn in the company of the devas of the cloud-dwelling order!’] → The threefold good conduct (tividha sucarita) → Giving (dāna) → Uposatha observance.

There is some inconsistency in the Suttas on whether the threefold conduct or giving is more significant, or if both factors are necessary. SN 32.3-52 includes both, SN 32.2 only the former, and AN 8.35 only the latter. It’s safe to say that fixed intention is indispensable; otherwise, a degree of leeway is accepted with the exact specifications. What’s stipulated is a degree of virtue (sīla) which consolidates into not merely ambivalent, but overall good conduct (sucarita). In other words, there is leniency regarding the exact form of virtue, but good virtue itself is non-negotiable. Take the simile of the lump of salt:

“Suppose a man would drop a lump of salt into a small bowl of water. What do you think, bhikkhus? Would that lump of salt make the small quantity of water in the bowl salty and undrinkable?

Yes, Bhante. For what reason? Because the water in the bowl is limited, thus that lump of salt would make it salty and undrinkable.

But suppose a man would drop a lump of salt into the river Ganges. What do you think, bhikkhus? Would that lump of salt make the river Ganges become salty and undrinkable?

No, Bhante. For what reason? Because the river Ganges contains a large volume of water, thus that lump of salt would not make it salty and undrinkable.”

AN 3.100

We can take the same sense with virtuous behavior; the less we cultivate, the more bitter our pool of kamma becomes56. We should strive to expand our pool of bright kamma (sukka kamma) to be as boundless as the river Ganges, making our dark kamma (kaṇha kamma) less gustable. Therefore, we can condense the factors into two parts:

Setting the explicit intention (adhiṭṭhāna) → Good virtue (kalyāṇa sīla)

The Role Of Cloud Devas (Valāhakas) In Meditative Practice

In a Western Buddhism focused on ‘deep’ and ‘introspective’ practice, the four foundations of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna), insight meditation (vipassanā), etc., take center stage. However, there is an entire world of contemplated practice not accounted for in the popular Western consciousness. Not that these practices are insignificant, but rather that these intensive subjects aren’t the full extent of the Buddha’s teaching..

Post-canonical commentarial texts such as the Visuddhimagga and Abhidhammattha-saṅgaha layout 40 types of meditative subjects (kammaṭṭhāna), ranging from visual objects (Kasiṇa) to death (maraṇasati)57. This taxonomy is a subject of many critiques, given its incongruence with the Suttas [e.g., the descriptions of the Jhanas and loving-kindness (metta) meditation are often disputed]. While the topic is worthy of discussion in its own right58, Buddhaghosa’s59 classification of Kammaṭṭhāna highlights a key point: The Buddha’s expansive toolkit of meditative contemplation extends far beyond the mainstream Western awareness.

While all of these subjects are worth exploring, the one especially relevant to the topic at hand is the recollection of deities/devas (devatānussati). This contemplation serves five main purposes:

Momentary suppression of the three defilements (mūla-kilesā) of greed (lobha), hatred (dosa), and delusion (moha).

Basis for the development of concentration (samādhi)

Momentary suppression of the fetters (saṃyojanāni) of sensual desire (kāmacchanda) and ill will (byāpāda).

A basis for more intensive practice.

Quelling the fear of death.

Before I delve any further, I must preface that this practice necessitates a certain level of preliminary development; otherwise, the contemplation will be fruitless. The entire point of the practice stems from recollecting the wholesome qualities (to be elaborated below) in yourself and taking the devas as witnesses. In other words, no good qualities = no recollection of devas. It’s like taking your abundant wealth as an object of recollection; you need to have the money in the first place. Many of the discourses regarding this practice were expounded by the Buddha to Mahānāma the Sakyan, a male lay disciple (upāsaka) who had already attained the status of stream enterer (sotāpanna)60, a stage of enlightenment at which it becomes no longer possible for rebirth in a lower realm to occur (SN 55.8). It’s made clear in the canon that the recollection is intended for practitioners with abundant virtue; it’s not just something anyone can pick up on the spot. To add further credence, the Visuddhimagga asserts this much outright:

“These six recollections61 succeed only in noble disciples62. For the special qualities of the Enlightened One, the Law63, and the Community, are evident to them; and they possess the virtue with the special qualities of untornness, etc., the generosity that is free from stain by avarice, and the special qualities of faith, etc.64, similar to those of deities.”

Vism VII, 121

However, Buddhaghosa continues to write that an ‘ordinary man’ can still derive fruitfulness from the practice, even shockingly asserting that one could attain Arahantship from the insight cultivated from the recollection. Objectively speaking, there is no account in the Suttas of these six Anussati practices culminating in enlightenment. Regarding the former claim, this is left somewhat ambiguous in the canon.

“Still, though this is so, they can be brought to mind by an ordinary man too, if he possesses the special qualities of purified virtue, and the rest. For when he is recollecting the special qualities of the Buddha, etc., even only according to hearsay, his consciousness settles down, by virtue of which the hindrances are suppressed. In his supreme gladness he initiates insight, and Concentration (samádhi) he even attains to Arahantship, like the Elder Phussadeva who dwelt at Kaþakandhakára65.

That venerable one, it seems, saw a figure of the Enlightened One created by Mára. He thought, ‘How good this appears despite its having greed, hate and delusion! What can the Blessed One’s goodness have been like? For he was quite without greed, hate and delusion!’ He acquired happiness with the Blessed One as object, and by augmenting his insight he reached Arahantship.”

Vism VII, 127 & 128

Recollection Of Deities (Devatānussati)

This is the basic formula for the practice of recollection of deities:

“…you should recollect the deities thus: ‘There are devas (ruled by) the four great kings66, Tavatimsa devas, Yama devas, Tusita devas, devas who delight in creation, devas who control what is created by others, devas of Brahma’s company, and devas still higher than these. There exists in me too such faith as those deities possessed because of which, when they passed away here, they were reborn there; there exists in me too such virtuous behavior...such learning ...such generosity ...such wisdom as those deities possessed because of which, when they passed away here, they were reborn there.’ When a noble disciple recollects the faith, virtuous behavior, learning, generosity, and wisdom in himself and in those deities, on that occasion his mind is not obsessed by lust, hatred, or delusion; on that occasion his mind is simply straight, based on the deities. A noble disciple whose mind is straight gains inspiration in the meaning, gains inspiration in the Dhamma, gains joy connected with the Dhamma. When he is joyful, rapture arises. For one with a rapturous mind, the body becomes tranquil. One tranquil in body feels pleasure. For one feeling pleasure, the mind becomes concentrated.”

AN 11.11

The five qualities of contemplation are:

Faith (saddhā)

Virtuous Behavior (sīla)

Learning (suta)

Generosity (cāga)

Wisdom (paññā)

The Abhidhammaṭṭha-saṅgaha67 frames the recollection of these qualities in relation to devas as such:

“'The recollection of the devas is practised by mindfully considering: ‘The deities are born in such exalted states on account of their faith, morality, learning, generosity, and wisdom. I too possess these same qualities.’ This meditation subject is a term for mindfulness with the special qualities of one's own faith, etc., as its object and with the devas standing as witnesses.”

“Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma” by Bhikkhu Bodhi (p.g. 336)

To simplify, and concerning Valāhakas specifically, the practice goes as follows:

Possess a certain degree of the five qualities68 → Recollect those qualities within yourself, to the extent to which they are present[‘There exists in me such faith, virtuous behavior, learning, generosity, and wisdom’] → Recollect the qualities to the exent to which they are present within the Valāhakas[‘Those deities possessed (these qualities) because of which, when they passed away here, they were reborn there (in the company of the devas of the cloud-dwelling order69)] → Recollect the qualities with yourself and within the Valāhakas→ The fruit of the practice arises[As described in AN 11.11].

Fruits (Phala) Of The Practice

As outlined previously, Devatānussati serves five main benefits to the practitioner as expounded in the Suttas. The basic template includes the following excerpt with little variability between the multiple Suttas on this recollection.

“…you should recollect the deities thus: There are devas (ruled by) the four great kings…When a noble disciple recollects the faith, virtuous behavior, learning, generosity, and wisdom in himself and in those deities, on that occasion his mind is not obsessed by lust, hatred, or delusion; on that occasion his mind is simply straight, based on the deities. A noble disciple whose mind is straight gains inspiration in the meaning, gains inspiration in the Dhamma, gains joy connected with the Dhamma. When he is joyful, rapture arises. For one with a rapturous mind, the body becomes tranquil. One tranquil in body feels pleasure. For one feeling pleasure, the mind becomes concentrated.”

AN 11.11

This is notable due to its heavy overlap with the seven factors of enlightenment (satta bojjhaṅgā).

“And how does a bhikkhu, based upon virtue, established upon virtue, develop the seven factors of enlightenment? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops the enlightenment factor of mindfulness, which is based upon seclusion, dispassion, and cessation, maturing in release. He develops the enlightenment factor of discrimination of states ... the enlightenment factor of energy ... the enlightenment factor of rapture ... the enlightenment factor of tranquillity ... the enlightenment factor of concentration ... the enlightenment factor of equanimity, which is based upon seclusion, dispassion, and cessation, maturing in release. It is in this way, bhikkhus, that a bhikkhu, based upon virtue, established upon virtue, develops the seven factors of enlightenment, and thereby achieves greatness and expansiveness in (wholesome) states.”

SN 46.1

Here we find a parallel with six out of the seven total factors between the two excerpts, excluding equanimity (upekkhā). Below is a chart showing the exact correlations:

Mindfulness (sati) → “You should recollect the deities thus: There are devas (ruled by) the four great kings.”

Discrimination of states (dhammavicaya) → “When a noble disciple recollects the faith, virtuous behavior, learning, generosity, and wisdom in himself and in those deities.”

Energy (viriya) → “On that occasion his mind is simply straight, based on the deities.”

Rapture (pīti) → “A noble disciple whose mind is straight gains inspiration in the meaning, gains inspiration in the Dhamma, gains joy connected with the Dhamma. When he is joyful, rapture arises.”

Tranquillity (passaddhi) → “For one with a rapturous mind, the body becomes tranquil.”

Concentration (samādhi) → “One tranquil in body feels pleasure. For one feeling pleasure, the mind becomes concentrated.”

Equanimity (upekkhā) → No overlap.

The caveat of equinimity being unattainable through the means of Devatānussati is crucial, as it shows how the recollection cannot culminate in Arahantship, as it could have otherwise. This is because upekkhā requires a contemplation that would entail not just tranquility and concentration, but outright dispassion (virāga). This quality is developed through mindfulness of the world's fragility, which uncovers the futility of clinging to anything in the world. The Ānāpānasati Sutta makes this clear in this section:

“Bhikkhus, on whatever occasion a bhikkhu trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating impermanence'; trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating impermanence'; trains thus: "I shall breathe in contemplating fading away'; trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating fading away'; trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating cessation'; trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating cessation'; trains thus: 'I shall breathe in contemplating relinquishment'; trains thus: 'I shall breathe out contemplating relinquishment' - on that occasion a bhikkhu abides contemplating mind-objects as mind-objects, ardent, fully aware, and mindful, having put away covetousness and grief for the world. Having seen with wisdom the abandoning of covetousness and grief, he closely looks on with equanimity, That is why on that occasion a bhikkhu abides contemplating mind-objects as mind-objects, ardent, fully aware, and mindful, having put away covetousness and grief for the world.”

MN 118

As stated in the above Sutta, only one who sees with wisdom the abandoning of covetousness (abhijjhā) and grief (domanassa) develops upekkhā. This could be categorized as an insight (vipassanā) practice, unlike Devatānussati, which culminates at samādhi and momentary suspension of sensual desire (kāmacchanda) and ill will (byāpāda). As Bhante Suddhāso adds (referring to Devatānussati), “this can also be a very useful practice if one is feeling depressed or low self-esteem70.”

“ …[Same as in AN.11.11]… on that occasion his mind is simply straight. He has departed from greed, freed himself from it, emerged from it. ‘Greed,’ friends, is a designation for the five objects of sensual pleasure. This noble disciple dwells with a mind entirely like space: vast, exalted, measureless, without enmity and ill will. Having made this a basis, too, some beings here become pure in such a way.”

AN 6.26

This last section on non-ill will runs similarly to loving kindness (mettā) practice.

“And toward the whole world one should develop loving-kindness, a state of mind without boundaries— above, below, and across— unconfined, without enmity, without adversaries.”

Sn 1.8

The correlation could allude to how Devatānussati can be used as a basis for more intensive cultivation, which would then carry the potency to guide the practitioner to deliverance, as the Mettā Sutta culminates in Arahantship.

“Not taking up any views, possessing good behavior, endowed with vision, having removed greed for sensual pleasures, one never again comes back to the bed of a womb.”

Sn 1.8

Bhante Suddhāso reiterates this in his discussion, as he speaks on how Devatānussati can be combined with Mettā Bhāvanā, in the context of developing Mettā for the deities.

An additional benefit of Devatānussati is the diminishing of the fear of death. This is expounded in a discourse given by the Buddha to Mahānāma, after he became anxious due to his muddled mindfulness. It should be noted that Mahānāma “was at least a stream-enterer, possibly a once-returner71,” according to Bhikkhu Bodhi’s gloss (CDB 1957) at the time this dialogue took place.

“'If at this moment I[Mahānāma] should die, what would be my destination, what would be my future bourn?' ‘Don't be afraid, Mahanama! Don't be afraid, Mahanama! Your death will not be a bad one, your demise will not be a bad one. When a person's mind has been fortified over a long time by faith, virtue, learning, generosity, and wisdom, right here crows, vultures, hawks, dogs, jackals, or various creatures eat his body, consisting of form, composed of the four great elements, originating from mother and father, built up out of rice and gruel, subject to impermanence, to being worn and rubbed away away, to breaking apart and dispersal. But his mind, which has been fortified over a long time by faith, virtue, learning, generosity, and wisdom-that goes upwards, goes to distinction72.”

SN 55.21

At the end of the Visuddhimagga’s section of recollection of dieties, it is further stated that one devoted to Devatānussati becomes dearly loved by the dieties73.

“And when a bhikkhu is devoted to this recollection of deities, he becomes dearly loved by deities. He obtains even greater fullness of faith. He has much happiness and gladness. And if he penetrates no higher, he is at least headed for a happy destiny.

Now, when a man is truly wise,

His constant task will surely be

This recollection of deities

Blessed with such mighty potency”

Vism VII, 118

The Buddha also exalted Mahānāma to practice Devatānussati regardless of circumstance.

“Mahanama, you should develop this recollection of the deities while walking, standing, sitting, and lying down. You should develop it while engaged in work and while living at home in a house full of children.”

AN 11.12

What The Fruits (Phala) Of The Practice Are Not

Devatānussati never culminates at Jhānanic states in the Suttas, further denied by the Abhidhammattha-saṅgaha and Visuddhimagga74. This is due to the fundamental incompatibility of these two practices, as the following template from the Anupada Sutta shows.

“Here, bhikkhus, quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, Sariputta entered upon and abided in the first jhana, which is accompanied by applied and sustained thought, with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion.”

MN 111

The rapture and pleasure of Devatānussati isn’t born of seclusion, but rather the recollection itself, which then leads to seclusion from sensual desires and unwholesome states.

Bhante Suddhāso’s Misinterpretation

In his livestream discussion on Devatānussati, Bhante Suddhāso makes the following statement: “As the Buddha mentions at the end here, one who practices this way has entered the stream of the Dhamma, the dhammasota. This indicates that this is also a way of approaching stream entry75.”

This is the Pali root that Suddhāso is referencing76:

“ayaṃ[this person] vuccati[to be said or called], mahānāma, ariyasāvako[disciple of the noble ones] visamagatāya[troubled] pajāya[population] samappatto[balanced] viharati[lives], sabyāpajjāya[afflicted] pajāya[population] abyāpajjo[unafflicted] viharati[lives], dhammasotasamāpanno[who has entered the stream of the Dhamma] devatānussatiṃ[recollection of (the qualities of) divine beings] bhāveti[cultivates].”

AN 11.11

Here are English translations of the same line from three different Pali scholars:

Bhikkhu Bodhi: “This is called a noble disciple who dwells in balance amid an unbalanced population, who dwells unafflicted amid an afflicted population. As one who has entered the stream of the Dhamma, he develops recollection of the deities.”

Thanissaro Bhikkhu: “Of one who does this, Mahanama, it is said: ‘Among those who are out of tune, the disciple of the noble ones dwells in tune; among those who are malicious, he dwells without malice; having attained the stream of Dhamma, he develops the recollection of the devas.’”

Bhikkhu Sujato: “This is called a noble disciple who lives in balance among people who are unbalanced, and lives untroubled among people who are troubled. They’ve entered the stream of the teaching and developed the recollection of the deities.”

The root text, along with the former two English translations, clearly indicates that stream entry is preliminary, not a result, in the context of this line. To add further credence, Mahanama was a stream enterer while this discourse took place.

The three fetters abandoned by the stream enterer (sotāpanna) are identity view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi), doubt (vicikicchā), and attachment to rites and rituals (sīlabbata-parāmāsa). It is hard to see how a practice of recollection of the devas would serve to completely surmount these fetters.

All of this leads me to conclude that Bhante Suddhāso has misinterpreted the text, and that stream entry is not a result of Devatānussati. If the inverse were true, this would have doubtlessly been made abundantly clear from the Suttas, which it is not.

Conclusion

So, what is the Dhamma in clouds, and what are the spiritual benefits of recollecting them?

From what I’ve gathered from my research, there are four main points:

A virtuous being can call on them at the appropriate times of assistance (Ja-a 75).

Setting one’s intention (adhiṭṭhāna) on rebirth in the company of cloud-dwelling devas leads to virtuous behavior such as good conduct and generosity (SN 32.3-52).

The practice of recollecting the cloud-dwelling deities (Devatānussati) culminates in concentration (samādhi), temporary suppression of the defilements (mūla-kilesā), sensual desire (kāmacchanda), and ill will (byāpāda). It can also alleviate the fear of death (AN 6.26).

Devatānussati can be used as a basis for more intensive practice, such as loving kindness meditation (mettā bhāvanā), which would then culminate in Arahantship (Sn 1.8).

Hopefully, I have been able to elucidate the doctrinal depth that even a seemingly trivial subject like cloud devas carries. Far from just world-building fluff (pun intended), the Valāhakas serve as a gateway to the expansive world of Buddhist cosmology, ethics, meditation, and soteriology.

Final Thoughts

For anyone who made it this far in this rather lengthy article, I’d like to offer my most sincere thanks. This post was more intensive than my previous ones and required heavy research. Hopefully, the depth of research is reflected in the quality. I learned a lot from researching the topic, and it was an enjoyable process. I do apologize in advance for any potential mistakes, spelling errors, etc., present in this post.

If you’d like to see more deep dives like this, consider subscribing to Chuddha Productions.

If you’d like to share my research with others, consider sharing this post.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please leave a like, and if you’d like to further the discussion in the comments or just have any general thoughts, feel free to comment below.

Here’s a GoFundMe for Starved Palestinian Kids in North Gaza:

Thank you, and peace and Metta to all ✌️

All translations used from the Saṃyutta Nikāya, Aṅguttara Nikāya, and Abhidhammattha-saṅgaha are taken from Bhikkhu Bodhi. The Dīgha Nikāya is translated by Maurice Walshe, the Visuddhimagga by Bhikkhu Nāņamoli, the Dīrgha Āgama by Shohei Ichimura, and the Jātaka-aṭṭhakathā by T. W. Rhys Davids, Robert Chalmers, and H.T. Francis, with W.H.D. Rouse and E.B. Cowell, and revised by Ānandajoti Bhikkhu. I am aware that some of these texts are post-canonical and have ensured that I do not stray too far from the Suttas.

This article, published by the Secular Buddhist Network, reflects many of the fundamental issues with a strictly secular approach. I would also add that the interpretation hinges on rather naive assumptions and a generous interpretation of the canonical text used to justify a pre-held ontological framework.

The original list is in SN 32.1.

This line highlights a key aspect of the celestial experience: its superiority over even the most profound human experience (MN 75).

It would be tempting to draw a comparison to climate change, which is accelerated by human immorality; however, the devas notably have a degree of control over the weather (not long-term weather averages as the term ‘climate’ implies), even then, they are not solely in charge, as Punnadhammo elucidates.

“Mighty water” is Walshe’s rendering of the Pali term “rahada,” translated as lake by Bhikkhu Sujato.

One of the four great continents (Mahādīpas), northern Kuru (uttarakuru), is located north of Mount Sineru (sumeru) and is described in detail in the Āṭānāṭiya Sutta (DN 32) and later commentaries. It holds the great royal city of Alakamandā, the dwelling place of Vessavaṇa, and the meeting grounds of his subordinate Yakkhas. For more information, check out this video.

Nāgas are dragon or serpent-like earth-dwelling celestial beings. They usually reside among water sources and mountain ranges. A Nāga king is a powerful being in this class. See this wisdom library entry for more info.

The Wheel-Turning Monarch (pali: cakkavatti). See the Cakkavatti‑Sīhanāda Sutta (DN 26).

Referred to as Lake Anotatta (literally meaning ‘unheated’) in the Pali canon (Thag 6.10), this is one of the seven great mythical lakes at the foot of the Himalayas (Himavā) in Buddhist cosmology. See this Palikanon entry for more info.

See SN 2.9 and SN 2.10 for more on Rāhu, king of the asuras.

Also referred to as Kuvera (DN 32).

Bhikkhu Bodhi characterizes Pajjuna simply as “the deva-king of rain clouds” (CDB 374); however, he is depicted as also reigning over storm devas in multiple texts, as shown later on (DN 20, Ja-a 75).

Also referred to as Indra or Inda (DN 32).

The following diagram was based on this template.

An interesting side note is that Pajjunna has many parallels throughout other mythologies, most directly with Parjanya, the Vedic god of rain, thunder, and lightning, just as described in the Pali canon. Other parallels are listed in this Wikipedia article on Parjanya.

The name is rendered “Pajunna” in Walshe’s DN and “Pajjuna” in the online translation of the Ja 75 verse; however, I prefer to use “Pajjunna,” as rendered by Bhikkhu Bodhi in CDB.

This Sutta offers a rare example of the Buddha instructing his disciples on the management of suffering through external means, calling upon devas to alleviate the distress inflicted by unwholesome celestial beings, rather than relying solely on internal practice.

The Jātaka, or Jātaka tales, are a collection of 547 poems recounting stories of the Buddha’s past lives.

The commentary also elaborates that the Buddha’s wish to bathe served a dualistic purpose; he took note of how “the fishes and the turtles were being destroyed,” and out of compassion, he set the intention: “This day must I cause rain to fall.”

This is an indicator that a karmically or spiritually significant event has taken place.

This alludes to the crows drowning in the newly formed mass of water.

This ‘grief’ is referring to the crows’ inability to catch the fish.

King Vessantara is the Bodhisatta in this specific story.

In Pali, the verse is “vuṭṭhidhāraṁ[a stream of rain] paveccanto[causing to pour forth] devo[the god] pāvassi[rained] tāvade[at that moment; instantly].” Notably, without mention of a named god.

Here’s a link to the original poem if you’d like to read it for yourself; however, it’s rather lengthy.

This seems reminiscent of Indra (one of Sakka’s epithets), who is the god of weather in Hinduism, adding further credence to Sakka being the figure referenced in Ja 547.

Early Buddhist Texts.

To avoid any potential confusion, I must clarify that this paragraph is not from the Pali canon, but from the Kangyur of the Tibetan Buddhist canon.

This is red Tārā, also referred to as Kurukullā, characterized by qualities of magnetism, power, and enchantment. For further information, check out this video.

This isn’t to say that one must blindly accept every Sutta, but rather that to disregard without critical evaluation, simply on the basis that the text does not accord with pre-held notions, is ill-advised.

This affliction can be interpreted as physical or psychological, similar to other evil deities such as Māra.

Another strategy against antagonistic spirits is cultivating loving-kindness (metta). It’s expounded in AN 8.1 and AN 11.15 that cultivating loving-kindness leads to the benefits of “one is pleasing to spirits; deities protect one…” As Bhikkhu Bodhi explains, the latter Sutta is also used as a protective verse.

Walshe shares an excerpt from the commentary of DN 32 (i.e., the Dīgha Aṭṭhakathā) which details the spiritual and cultural applications of these verses:

“DA, however, advises the use of the Metta Sutta [Sn 1.8] in the first place, then the Dhajagga [SN 11.3] and Ratana Suttas [Sn 2.1]. Only if, after a week, these do not work, should the Atanatiya be resorted to…

This Sutta is much used on special occasions in the countries of Theravada Buddhism. Thus in Thailand it is chanted at the New Year…”

LDB 613

Coming from an atheistic background, I struggle with this myself as well.

Although not mentioned explicitly, it can likely be inferred that they are both cloud devas as well, as nothing indicates otherwise.

A four-times-a-month observance of the 8 precepts, following the lunar calendar. Here’s a 2025 calendar showing the exact days as well as holidays.

The first three factors relate to mundane virtue (lokiya sīla) and some degree of higher mind (Adhicitta-sikkhā, but largely abstain from any component of the threefold training (tissoṅkhaṃ sikkhā): higher mind (adhicitta-sikkhā), higher wisdom (adhipaññā-sikkhā), and higher virtue (Adhisīla-sikkhā), which disciples undertake for the realization of enlightenment (Arahantship) (See AN 3.89 for further elaboration). For the fourth factor in rebirth, as elaborated in the Cetokhila Sutta (MN 16), aspiration for rebirth among devas is one of the five shackles in the heart (cetaso vinibandhā). This isn’t to say that the endeavor required for higher rebirth is un-noteworthy, but that the ambition for company among devas and freedom from the cycle (Saṃsāra) are mutually exclusive.

It’s noteworthy that the word “good” is used to refer to conduct conducive to rebirth among the Valāhakas and Gandhabbas, while “ambivalent” is used to refer to Nāgas and Supaṇṇas. The latter term denotes a quality of mixedness or contradiction, while the former is overall moral righteousness. This detail may seem minor, but it reveals one of the prime characteristics of Buddhist cosmology: the abodes become progressively more refined as they progress, according to the kamma of beings in their past lives. While Nāgas and Supaṇṇas are ascribed to various crude birthing processes, the Valāhakas and Gandhabbas are of spontaneous birth.

This shows how setting an explicit determination for rebirth among the Valāhakas, along with following the prescribed wholesome conduct, directly leads to this abode.

See AN 10.176, AN 10.216, AN 10.217, etc. for further elaboration.

See AN 8.39 for a full list of the precepts.

The Sīgālovāda Sutta lays out “six dangers attached to addiction to strong drink and sloth-producing drugs” (cha imā ādīnavā surāmerayamajjapamādaṭṭhānassa):

“There are these six dangers attached to addiction to strong drink and sloth-producing drugs: present waste of money, increased quarrelling, liability to sickness, loss of good name, indecent exposure of one's person, and weakening of the intellect.”

DN 31

One with right view (sammādiṭṭhi) could discern these six dangers, albeit not the supermundane right view conducive to enlightenment. As expounded in AN 10.217, one who holds the right view understands “there is fruit and result of good and bad actions...”

This stock-listing of ten kinds of giving includes three out of the four requisites (cattāro paccayā) (see DN 2) for monastics: robes (cīvara), alms food (piṇḍapāta), lodging (senāsana), but curiously excluding medicinal requisites (bhesajja-parikkhāra). This might suggest that donation shouldn’t be relegated solely to monastics but to other beings as well.

See AN 5.34, AN 5.36, AN 2.141-143, etc. Generosity can also function as a meditation subject (cāgānussati), as elaborated in AN 6.25.

It’s perplexing how the phrase “He gives that gift to an ascetic or a brahmin” is used in this Sutta, but is excluded from the template directly referencing rebirth among Valāhakas, even though the gifted articles remain identical. Perhaps this implies how rebirth in the company of cloud-dwelling devas is held to a lesser standard. See MN 142, “The Exposition Of Offerings,” for a list of the least and most beneficial types of giving.

Bhikkhu Bodhi elaborates that “these are the ancient brahmin rishis who were supposedly the composers of the Vedic hymns” (NDB 1779).

This description appears befuddling at first glance. For an explanation, I would refer to a comment made by user “Polarbear” on a Suttacentral discussion post:

“I think the idea is that if you give in order to further purify the mind for the sake of realizing nibbāna, that is the highest motive. Gladness and joy are more transitory states but if you use generosity as a means to cultivate a more stable purity of mind, then you can use that purity as a tool/equipment for attaining the as yet unattained. Something like that anyway.”

See this Dhammawiki page to learn more about the 31 planes of existence.

Obviously, you shouldn’t gift intoxicants, inappropriate or unrighteously obtained gifts, etc. (MN 142).

Given the austere nature of this practice, I’d suggest that it be done within a supportive community setting.

As mentioned in footnote 7, this path (magga) is fundamentally incompatible with the striving for enlightenment.

For exposition on the four types of kamma, see AN 4.232 and AN 4.233.

Pages 334 and 335 of the “Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma” by Bhikkhu Bodhi provide a breakdown of all 40 meditation subjects through an Abhidhamma analysis.

It’s important to note that our basis for accepting teaching shouldn’t solely rely on whether it’s written in the Suttas. The Buddha explicitly rejects this line of reasoning: “Come, Kalamas, do not go… by a collection of scriptures,” (AN 3.65). He instead exhorts us to accept teachings “when you know for yourselves: ‘These things are wholesome; these things are blameless; these things are praised by the wise; these things, if accepted and undertaken, lead to welfare and happiness,‘” (AN 3.65).

However, the former excerpt is seemingly contrasted by a later Sutta in the same collection (Aṅguttara Nikāya):

“In such and such a residence one elder bhikkhu is dwelling who is learned, an heir to the heritage, an expert on the Dhamma, an expert on the discipline, an expert on the outlines. In the presence of that elder I heard this; in his presence I learned this: This is the Dhamma; this is the discipline; this is the Teacher’s teaching! That bhikkhu’s statement should neither be approved nor rejected. Without approving or rejecting it, you should thoroughly learn those words and phrases and then check for them in the discourses and seek them in the discipline. If, when you check for them in the discourses and seek them in the discipline, (you find that) they are not included among the discourses and are not to be seen in the discipline, you should draw the conclusion: Surely, this is not the word of the Blessed One, the Arahant, the Perfectly Enlightened One. It has been badly learned by that elder.’ Thus you should discard it.”

AN 4.180

Should we accept teaching when we know it for ourselves, or as long as they are included among the discourses and disciplines? Firstly, the context of these two excerpts is a bit different. The former is addressed to householders, while the latter is addressed to Bhikkhus. It’s assumed that people who have gone forth would have developed adequate faith (saddhā) and confirmed confidence (aveccappasāda) in Dhamma to the extent that the former teaching has already been understood. Becoming a Dhamma practitioner entails an implicit discernment of what is wholesome (kusala) and unwholesome (akusala), along with what leads to welfare and happiness; what else would be covered in the discourses and monastic rules (vinaya) other than just this very topic? Given this context, consulting canonical texts is the most rational framework for approaching questionable teachings. However, what constitutes ‘discourses and disciplines’ is up to the personal interpretation of what texts are authoritative, and for that interpretation to be done faithfully, the context of the first excerpt is necessary. Therefore, I would view the former as the golden standard for acceptance of doctrine.

There is also the question of potentially ‘corrupted’ Suttas or later additions, such as some texts from the Dīgha Nikāya, Aṅguttara Nikāya, Jātaka Tales, etc.; however, this itself initiates a complex and nuanced discussion outside the subject at hand.

In short, the issue is far more nuanced than ‘Suttas are always right, and commentaries are always wrong’, as some reformist schools regard. Just as with any modern Buddhist teacher, you can accept some of their teachings and not all, given what you find reasonably applicable.

Buddhaghosa is perhaps one of the most influential philosophers in all of Theravada Buddhism, having authored the Visuddhimagga and many other commentarial works.

A stream enterer is the first of the four stages of enlightenment, guaranteeing liberation within the course of seven lives. The nuances of this specific stage, what it entails, and its prerequisites are intricately detailed within the canon and post-canonical literature. Here’s a recent article published by Doug Smith on this topic.

The six recollections (cha anussatiyo) consist of recollection of Buddha (Buddhānussati), Dhamma (dhammānussati), Saṅgha (saṅghānussati), Virtue (sīlānussati), Generosity (cāgānussati), and our primary subject: Devas (devatānussati).

Exactly what beings can be denoted as a noble disciple (ariyasāvaka) is subject to discord; see this discussion thread for a detailed discussion. What is certain is that it’s an epithet of a devoted practitioner.

Law means Dhamma (the teaching) in this context.

As will be covered later, these five qualities consist of Faith (saddhā), Virtue (sīla), Learning (suta), Generosity (cāga), and Wisdom (paññā).

This appears to be a commentarial anecdote, as I was not able to find any canonical text in line with this reference.

The Valāhakas fall under this categorization.

A concise manual of the Abhidhamma Piṭaka [one of the three great baskets of the Theravāda Pali canon (tipiṭaka)]

The cultivation of these qualities is discussed in the section on “Cause for Rebirth Among The Cloud Devas (Valāhakas)”.

The qualities most directly applicable to Valāhakas are the threefold good conduct(virtuous behavior in this context) and giving (generosity).

See this YouTube livestream discussion: “Recollection of Deities, with Bhante Suddhāso.”

A once-returner (sakadāgāmī) is the second stage of enlightenment, at which the being will be born once more in the human realm (manussaloka). Practitioners at this stage have eliminated three lower fetters and have weakened sensual desire and ill will.

“Goes to distinction” is a designation for heavenly rebirth in this context.

This distinction is never attributed to Devatānussati in the Suttas.

The Visuddhimagga explains this using Abhidhammarmic analysis:

“ …the jhána factors arise in a single conscious moment. But owing to the profundity of the special qualities of faith, etc., or owing to his being occupied in recollecting special qualities of many sorts, the jhána is only access and does not reach absorption. And that access jhána itself is known as ‘recollection of deities’ too because it arises with the deities special qualities as the means.”

Vism VII, 117

This evaluation hinges on the commentarial inventions of Access Concentration (upacāra-samādhi) and Absorption Concentration (appanā-samādhi). The former is preliminary work for Jhānaic states, while the latter encapsulates them. See Vism III, 6. If we take the Sutta template, the first section: “Here, bhikkhus, quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states” corresponds with Upacāra-Samādhi. This would accord with the Suttas, as Devatānussati culminates in the momentary suppression of sensual desire and ill will (AN 6.26).

The root text and definitions are taken from Suttacentral, Digital Pāḷi Dictionary, and Digital Pali Reader.